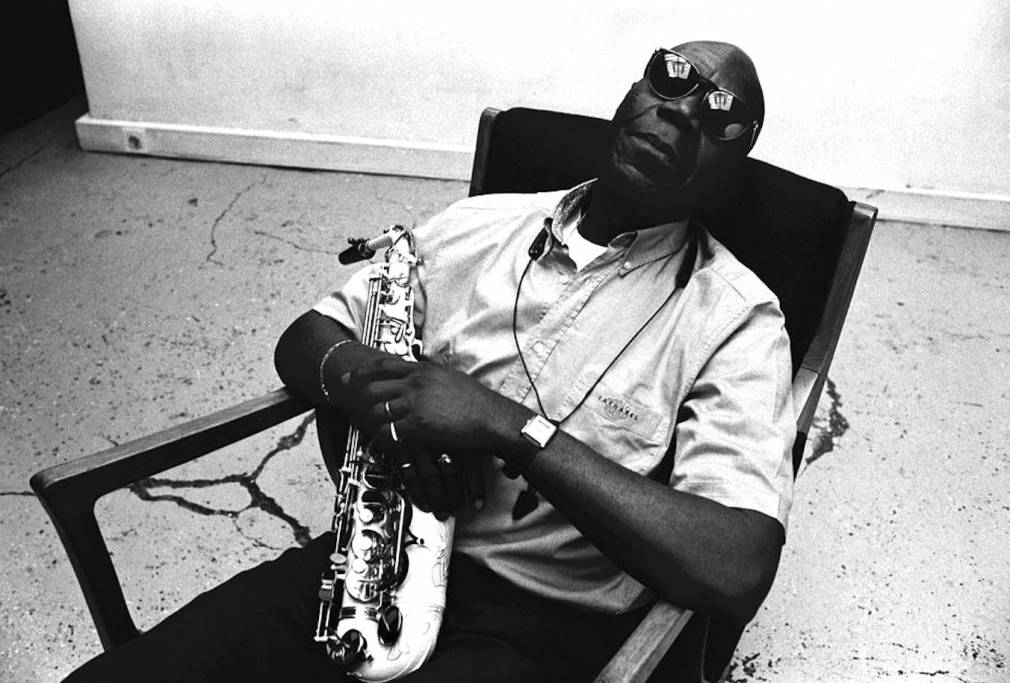

PAM pays tribute to Manu Dibango, who left us on March 24, 2020. The musician, a generous pioneer, has built bridges between Africa and the rest of the world. A look back at the first chapters of his fantastic novel-like life.

It was such a brutal awakening yesterday. We already knew the bastard had caught him – coronavirus – but since the latest news of his condition were good, we thought that the indomitable old lion was going to be able to close this file, once again. But not this time: at 86 years old, our African uncle is gone for good. He left for “a night at the village” (“Soir au village”, a song he recorded in 1974), to join the ancestors who await him: Le Grand Kallé, Rochereau, Nino Ferrer, Ray Barretto, Alain Bashung and Jacques Higelin… and so many other musicians with whom he shared the stages and wrote some of the most beautiful pages in the history of music, and in our History.

This is an article I would have preferred never to write, but since our uncle is gone, the time has come to honor his memory, rummaging through some of the chapters of his novel-like long life. I’ll open the first ones only, quoting his own words.

Jazz music, rillettes and palm wine

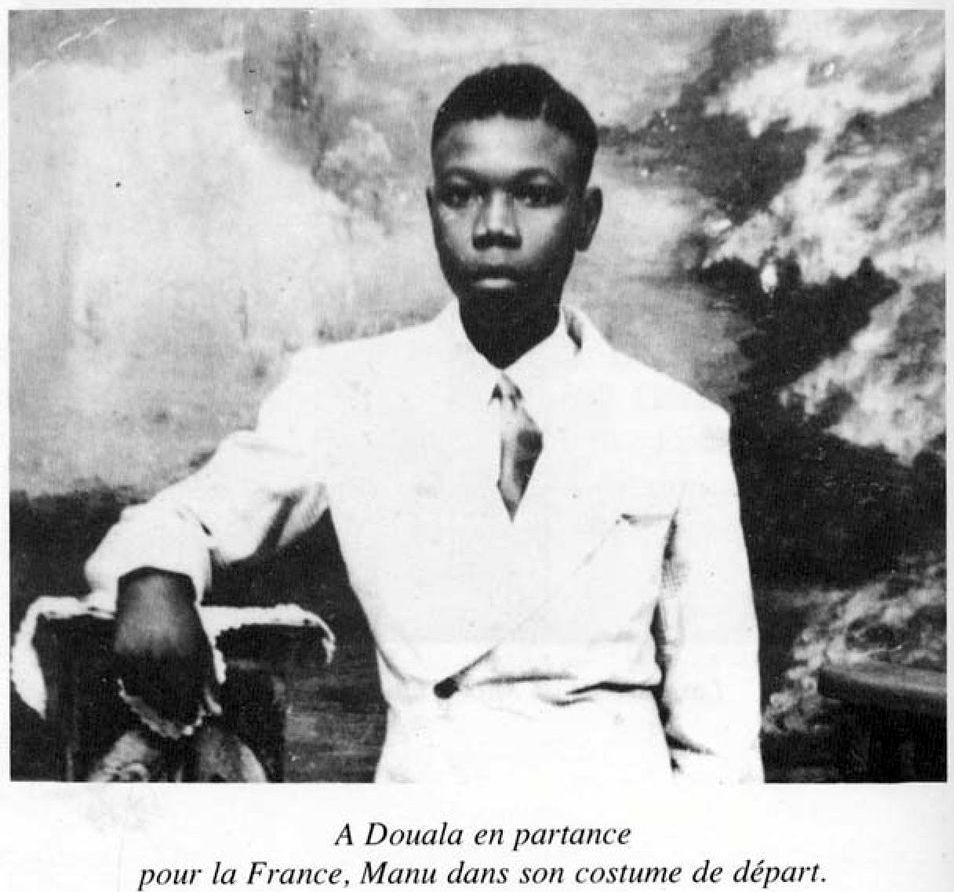

Emmanuel Ndjoke Dibango believed in the power of fate, which had given him the chance to experience so many adventures. To start, that of leaving Douala, Cameroon, where he was born in 1933, and where he had experienced his first musical excitement at church. His father was the treasurer, and his mother the choirmaster. But he awaited “less the pastor’s sanctimonious twaddle than the moment when the organist, with his little horn-rimmed glasses, started pumping on the harmonium,” he told us a few years ago. Yet a music career was out of question in a family who decided to send their child to study in France so that he would – inevitably, they thought – come back as a lawyer or doctor… “Before leaving they make you swear never to marry a foreigner – you see, [France] is not the only place where mixed marriages are not welcome –, so they organize ceremonies and make you swear. But, hey, when puberty rings at your door, what do you do with the promise you made at 15?” His father sent him to a family of primary school teachers in the small French village of Saint-Calais, Sarthe, along with his outfit and, by way of grant, three kilos of coffee to offer to his guests – a precious and rare commodity at the time.

“Back then, when your father sent you a letter, it took a month before you’d receive it, so when they yelled at you, there was a month-long delay!” he liked to remember, laughing. During the summer holidays, he went to colonies organized for young Cameroonians (who were French citizens at the time, Manu liked to point out). This is where his elder Francis Bebey introduced him to jazz music. Soon, Manu chose the saxophone, and while continuing his studies, he began to play at Le Monaco, a jazz club in Reims, France. There, dressed in a Lester Young-styled suit-and-hat outfit, he quickly forgot his homework and missed his high school diploma. When his father knew about it, he cut his son off completely – with a month’s delay: music is not a serious profession, my son. One of his Ivorian friends introduced him to his cousin Fax Clark, who ran a club in Brussels, Le Tabou. A good compromise, he thought, so he could perform at night and continue with school during the day. But the nightlife quickly won over the daytime studies. He became the conductor of the orchestra of the club Les Anges Noirs (“The Black Angels”), forgetting about his studies, without knowing that history with a capital H, had reserved a path for him and would bring him back to Africa. Indeed, in January 1960, when French Cameroon had just gained its independence, the Congolese negotiated theirs in Brussels, during the “Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference”.

From Cha-cha to Twist, from Brussels to Léopoldville (Kinshasa)

Manu: “When Lumumba (and the others) arrived at the time of the Round Table Conferences, they traveled with Kabasele (and his orchestra, the African Jazz who recorded at that time the famous “Independence cha-cha”). Every evening, when they had finished speaking politics, the Tshombés, the Kalonjis, the Lumumbas… they would head to the club. Mobutu too… he was still a journalist at the time. I didn’t speak with Lumumba, but I did chat a lot with Bomboko, who was one of the few Congolese students who had been allowed to go to the University of Louvain [in Belgium]. Can you realize that in 1960, the Congo had no intellectuals? Student would generally drop out after the school certificate [a diploma 13-year-old students would pass before entering secondary education; Translator’s note], because the Belgians did not want them to go further. The only Congolese you would see in Brussels were houseboys whom Belgian families had brought back to show that they had succeeded… so among these rare students (there were four when I was there), was Bomboko who would come to the club. As he had no money, I paid him Coca-Colas – you know how big brothers do… and one day I turned on my TV set and I see Bomboko with King Baudouin [King of the Belgiums; TN]. They told me he was a minister and I said to myself: what the hell! This is when I woke up, and woke up to politics too.”

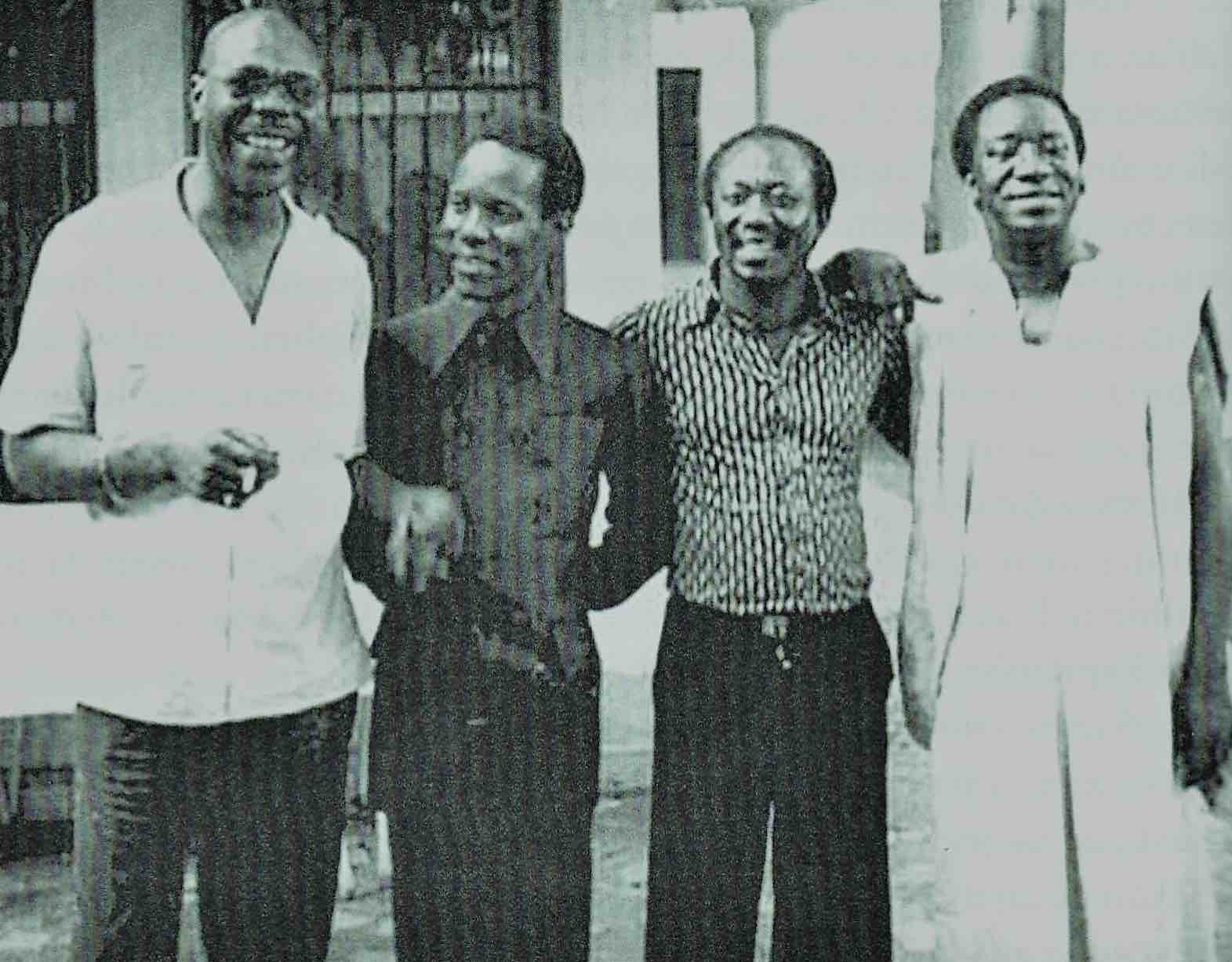

Kabasele would also often come to visit Manu, and eventually offered him to replace his ill saxophonist who stayed in Léopoldville (later renamed Kinshasa, in nowadays D.R. Congo), to record a series of albums during his stay in Brussels with the African Jazz. “So I went into the studio with him to play the sax and the piano. It was a big success there in Kinshasa, and I became famous thanks to the Kabasele recordings even though I had never set foot in Africa. It was the first time that an African orchestra recorded under the same conditions as the artists here [in Europe; TN].” In the meantime, the saxophonist was hired to play with the Cocoblicos orchestra for the Ivory Coast’s independence celebrations, on August 7, 1960.

Thanks to the success of the records he did with Kabasele, the boss of African Jazz offered to join him for a series of concerts in Africa. Manu Dibango then left for a month with Coco, his White spouse. They would stay there for two years.

“I didn’t know Africa. There I learned about Africa and how to play African music with Africans, in Africa.” And if the African rumba adopted the musician, he did not forget about jazz music, which was more the thing at the Afro-Négro, a Léopoldville-based club which he eventually took over, offering his wife the cashier position. It was at that time that he recorded some tracks for the Ngoma studio, including “Ekedy” and “Twist à Léopoldville”. He also brought his parents there, to whom he finally introduced Coco. His father convinced him to return to Cameroon, where he opened a club, the Tam-Tam, in 1963, bringing Congolese musicians with him. But the experience did not last long, as the obstacles multiplied, and the frequent unexpected police raids ruined the atmosphere and eventually ruined the business. “I was neither a politician nor a businessman, so it was time for me to get out of here,” recounted Manu. He went back to Europe, and chose to settle in Paris.

From the Wouri river to Paris, via New York and Abidjan

In Paris, Manu would play in ballrooms, and appeared every Tuesday in the Pigalle neighborhood, where musicians looking for a job in the orchestras awaited an offer, and he eventually embarked on a tour with Dick Rivers. The French rocker opened for one of French pop star Nino Ferrer’s shows, who offered Manu to substitute his organist. He played one concert in Liège, Belgium. Then no more news… Until “the-singer-who-wanted-to-be-a-Black” (Ferrer sang “je voudrais être un Noir”, i.e. “I’d like to be a Black”, in a 1966 song) stumbled upon him on the stage of a Montparnasse club, right in the middle of a sax solo. Their dialogue, which Manu liked to relate, remained in the history of music:

Nino Ferrer: “You never told me you played the sax!”

Manu: “Well you never asked me!”

The next day, Manu Dibango became his conductor. “I was the first non-North-American Black man to perform with a star here. The only person who represented people of color at the time was [French Caribbean singer] Henri Salvador.”

Few are the artists who, like him, have played with French and African stars alike. “I am exactly from both sides of the Mediterranean. I am a child of colonization…”

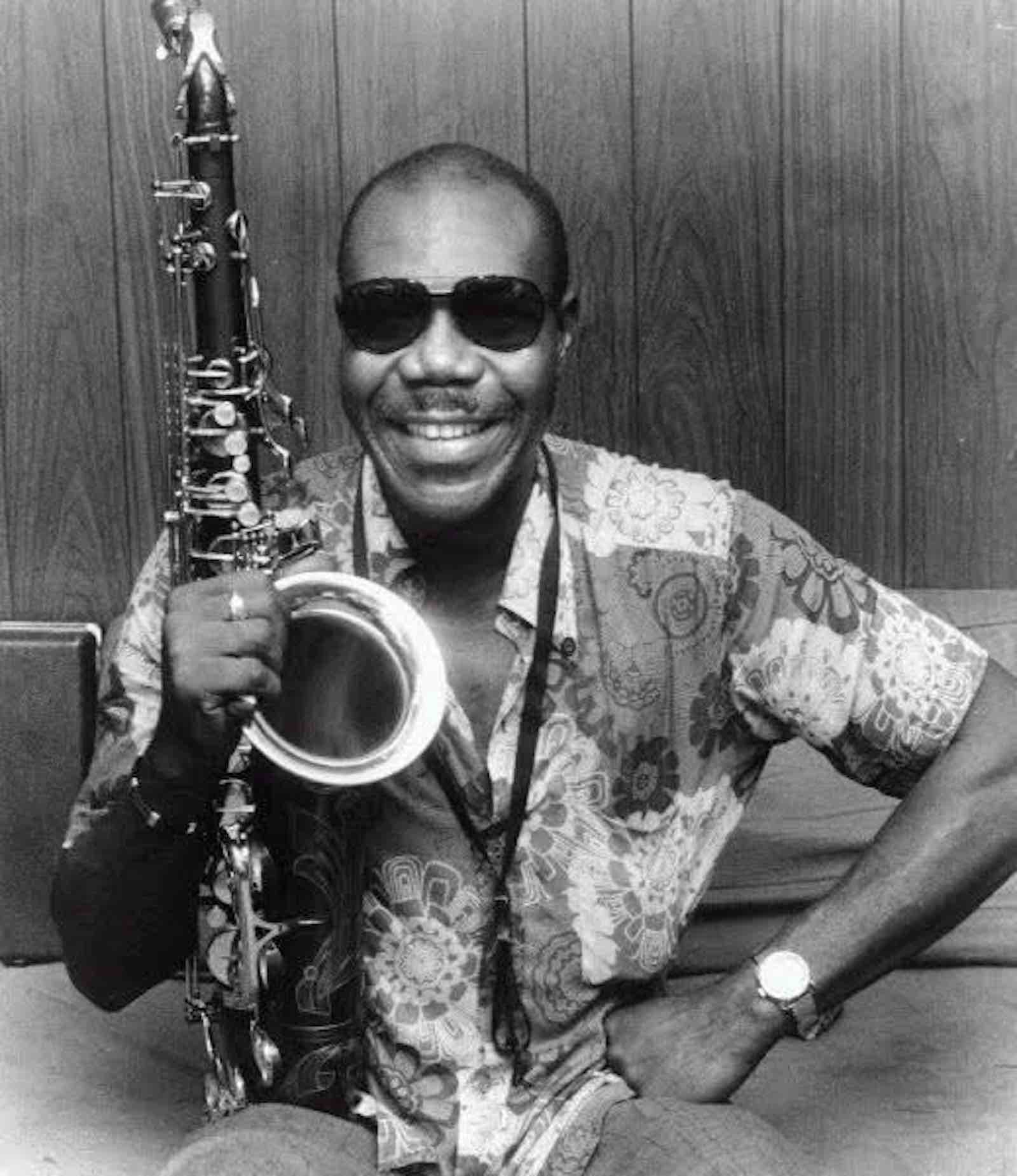

On the Cameroon side, the country organized the Africa Cup of Nations – CAF in 1972 and commissioned Manu to compose the competition’s anthem. He entered the studio to record it: “B-side is the best side: it’s something you don’t really count on, since when you go to the studio you want to record the A-side. But in the era of the 45 rpms, you had to invent anything so you had a B-side too. Nobody remembers the cup’s anthem, and since we lost it (against Congo-Brazzaville) nobody wanted to hear about that thing anymore. But at the time, African-Americans were going back to their roots – “Black and proud”, Shaft and all that… They were digging for African records in France, and in the lot was the famous 45 rpm. And the winner is…” Manu, of course!

The B-side song “Soul Makossa” reached the top of the US charts, and overnight, in 1974, Manu left the ballrooms for the Apollo Theater, Harlem’s legendary Black concert hall where all the greatests had performed. For ten evenings in a row, the elite of African-American artists (from Isaac Hayes to Barry White) hurried to see him perform, but also the boss of the Fania All Stars, since at the time, recalled Manu, “the Spanish Harlem, too, claimed its African roots.” He found himself on board for a crazy tour with the label’s All Stars: through the United States, but also Venezuela, Panama, and Puerto Rico where the concert was recorded and published on the famous New York-based label. “Johnny Pacheco, Ray Barretto, Cheo Feliciano… these are people I never even hoped to meet, let alone play with them”.

The crazy 1974 year ended with the famous Zaïre 74 festival which was to serve as a prelude to the Ali vs Foreman boxing fight. Manu went there with the Fania crew (including Celia Cruz), BB King, James Brown, and of course Franco and Rochereau, to name a few, without forgetting Miriam Makeba, the only artist from Africa who had met with success in the United States before Dibango.

Driven by his luck, Manu was called by president Houphouët-Boigny to conduct the Ivorian Radio Television Orchestra. “He wanted to have the best Africans in Ivory Coast, not just in music. It would be unimaginable today for an Ivorian to lead Cameroon’s orchestra. But at that time, the great Malian musician Boncana Maïga was the director of the arts center: so we were a Cameroonian and a Malian, and we took the best musicians from Ghana, Congo, etc. We even perform at Paris’ Olympia, and recorded an album.” Inevitably, the orchestra also had to compose songs for the visits of heads of state (like “Akwaba VGE” in honor of French president Giscard d’Estaing in 1977), and Manu even attended the “coronation” of Emperor Bokassa, who had asked Houphouët – his “third dad, after his biological father and De Gaulle”, liked to recall Manu, amused – to lend him his national orchestra.

A reserved man, Manu did not cover the circumstances that precipitated his departure from the Ivory Coast. But one understands that the pan-african diplomatic policy was not to the taste of everyone in the country, and probably not of all musicians. However, a new adventure awaited him.

Africa-upon-Seine, the comeback

In Paris, a Manu Dibango still haloed by his success and followed by his lucky star, recorded practically one album per year during the ’80s. The left entered in power, non-State radios multiplied, and the “worldwide sound system” – a concept so dear to Paris-based “free radio” Radio Nova – settled down. Suffice to say that he was a pioneer. In 1985, he was also one of those who organized the mobilization of artists to record Tam-Tam pour l’Éthiopie (“Tam-Tam For Ethiopia”), a record full of good intentions to help populations devastated by starvation. The man coming from not one single culture, but at least two, joined the Congolese artist Ray Lema who founded the Bwana Zoulou Gang, a band featuring French rock and pop stars Alain Bashung, Charlélie Couture and Jacques Higelin: an all-star gathering, just for one record!

Then his famous forgotten 1972 B-side unexpectedly resurfaced in 1982 when Michael Jackson used the chorus of “Soul Makossa” on his album Thriller, for the song “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin'”… without notifying the songwriter. The case would eventually be settled out of court, with a (financial) concession between the two parties. Jackpot! And jackpot again twenty years later, with Jennifer Lopez’s case. And another time… when Rihanna decided to cover the famous chorus, and mistakenly credited Michael Jackson (frankly, such lack of knowledge leaves one confused sometimes…).

To be continued

Manu’s novel is too long to be told in its entirety here. You can read it in his autobiography, Trois kilos de café (1989, Lieu commun ed.; English translation: Three Kilos of Coffee: An Autobiography, 1994, University of Chicago Press ed.). If he performed all genres, federated all the African artists around him (see the album Wakafrika), collaborated with all generations (let’s remember 2011 when Black Eyed Peas’ Wayne Beckford covered Manu’s songs), he always kept an immoderate taste for jazz music (he recorded a tribute album to Sidney Bechet), the ultimate cross-cultural music genre, both White and Black, African and Western… many different worlds between which he loved to build bridges, because he embodied them both, in the proper sense of the term. Like no one, he knew how to analyze and tell – always with lucidity, tenderness and humor –, the cultural, historical and emotional relations between France and Africa.

By writing these words, and reading his own words again, I realize how much we have just lost a whole section of our own history, which he was never reluctant to tell. Constantly punctuated with laughters. That too was part of his generosity. His legendary good humor was part of his good manners, and a daily contribution to what is often labeled today “peaceful coexistence” or “togetherness” [loose translation for the political French concept of “vivre ensemble”; TN], as if it were a museum object. I remember having the pleasure of seeing him perform with his accomplice Ray Lema on the piano, and himself on the sax, singing “Soma Loba” and old Congolese standards, like “Jamais Kolonga”. Delighted as two kids, with a smile that defied eternity. The eternity of the nights at the village, which he liked so much to sing. Goodbye, tonton. You will be truly missed.

*All the quotes are from an interview of “the doyen” (“the Elder”) by Vladimir Cagnolari and Ivorian journalist Soro Solo.

Article updated on March 24, 2021.